|

|

|

|

Name: Terry Vance Gilliam |

|

|

|

|

Name: Terry Vance Gilliam |

![]()

If there is one thing that gives Monty Python it's unique look it is the

weird and sometimes macabre animated inserts that link the sketches. These are supplied by Monty Python's very own Anglicised American.

Terry Vance Gilliam was born in the rural community of Medicine Lake, Minnesota on 22 November 1940. (Curiously those other purveyors of the

weird the Coen brothers also hail from Minnesota - perhaps it's something in the water?). His father, a travelling salesman for Folger's Coffee before

becoming a carpenter, had served in the last ever U.S. cavalry unit. Gilliam has two siblings, a brother (10 years younger, and now a detective with the Los Angeles Police Dept.), and a sister (2 years younger). It was because of his sister’s asthma that Gilliam’s family upped sticks and moved to California, (to the "other" side of the Hollywood sign) where Gilliam enrolled at Birmingham High School. Here Gilliam managed to achieve straight A’s in all subjects, as well as becoming president of the student body, senior prom king and was voted “Student Most Likely To Succeed”. More notably, Gilliam discovered Harvey Kurtzman’s irreverent and anti-establishment comic

MAD. This proved to be to Gilliam what The Goons was to many of the other Pythons – a source

of inspiration that would influence his work. Gilliam would also find inspiration in comedian Ernie Kovac's two television series

Ernie in Kovacsland, and The Ernie Kovacs Show - both stream of consciousness

shows. In 1958, Gilliam graduated from High School and entered Occidental

College on an academic scholarship funded by the Presbyterians (at one point

Gilliam considered becoming a missionary). There he majored in political science (after switching from physics then fine art).

At the same time, Gilliam was applying his talents to the college magazine

Fang – of which he became editor in his third year (turning it into an unashamed tribute to Harvey

Kurtzman).

Terry Vance Gilliam was born in the rural community of Medicine Lake, Minnesota on 22 November 1940. (Curiously those other purveyors of the

weird the Coen brothers also hail from Minnesota - perhaps it's something in the water?). His father, a travelling salesman for Folger's Coffee before

becoming a carpenter, had served in the last ever U.S. cavalry unit. Gilliam has two siblings, a brother (10 years younger, and now a detective with the Los Angeles Police Dept.), and a sister (2 years younger). It was because of his sister’s asthma that Gilliam’s family upped sticks and moved to California, (to the "other" side of the Hollywood sign) where Gilliam enrolled at Birmingham High School. Here Gilliam managed to achieve straight A’s in all subjects, as well as becoming president of the student body, senior prom king and was voted “Student Most Likely To Succeed”. More notably, Gilliam discovered Harvey Kurtzman’s irreverent and anti-establishment comic

MAD. This proved to be to Gilliam what The Goons was to many of the other Pythons – a source

of inspiration that would influence his work. Gilliam would also find inspiration in comedian Ernie Kovac's two television series

Ernie in Kovacsland, and The Ernie Kovacs Show - both stream of consciousness

shows. In 1958, Gilliam graduated from High School and entered Occidental

College on an academic scholarship funded by the Presbyterians (at one point

Gilliam considered becoming a missionary). There he majored in political science (after switching from physics then fine art).

At the same time, Gilliam was applying his talents to the college magazine

Fang – of which he became editor in his third year (turning it into an unashamed tribute to Harvey

Kurtzman).

After graduating, Gilliam spent a short time working for an advertising agency, before Kurtzman (to whom Gilliam had sent copies of

Fang) offered him a job as associate editor of his magazine Help! (during this time, John Cleese was touring New York with

Cambridge Circus, and was persuaded to appear in a Help!

photostory).

In 1965, Help! folded, and to avoid being drafted (the Vietnam War at this time was still going on), Gilliam enrolled in the National Guard, doing basic training in New Jersey (although stories say that much of his time was spent drawing flattering caricatures of the officers and working on the camp newspaper).

On his release, Gilliam went travelling in Europe, returning homeless and penniless to New York (where he ended up sleeping in the attic of Harvey Kurtzman’s house). Moving to Los Angeles failed to produce any employment, so in 1967, he moved again, this time to London.

In England, Gilliam secured a job working for the

Sunday Times Magazine (considered at the time an innovative publication – how times

change!), as well as freelancing for a few American comics. From there, Gilliam moved on to the job of artistic director for

The Londoner. Unfortunately, Gilliam again found himself unemployed when this folded.

Looking for a change of direction, Gilliam phoned John Cleese (the only person he knew

in television) and was pointed in the direction of producer Humphrey Barclay (a fellow

cartoonist) who in turn sent him in the direction of Eric Idle, now working with Messrs. Jones and

Palin on the children's television series Do Not Adjust Your Set (the

first time Gilliam walked on set, everyone remembers him wearing a fantastic

furry Afghan coat which Eric Idle adored!!!). Gilliam wrote a couple of sketches

and provided some animations for the third series of Do Not Adjust Your Set

before moving on to the show

We Have Ways of Making You Laugh (also with Eric Idle). Avoiding a second draft in America (Humphrey Barclay wrote to the U.S. Army saying Gilliam was indispensable), Gilliam

teamed up with 5 desperate artists writing a new show –

Monty Python’s Flying Circus.

Although Gilliam’s style of animation gave, and still gives, Monty Python it’s unique look, he picked the method because it was cheap, and (for someone who had done

little animation before) easy to learn. The results – made from cut-outs, (with noises and sound effects often provided by Gilliam himself huddled under a blanket using a cheap tape recorder), give the animations a slick, yet home-made look. Often he was just given the end of one sketch and the beginning of another, then left to his own

devices to get from one to the other, returning with them frequently on the day of recording. Gilliam provided another important role, balancing out the team (often supporting Jones and Palin, against the Cambridge

gang of Cleese, Idle and Chapman). This, and the fact that not being an Oxbridge graduate (or indeed from England), meant

that he could provide a new view of the world from the class-system obsessed world of the others. Gilliam only occasionally appeared in front of the camera

(for example as Cardinal Fang in the Spanish Inquisition sketch. Contrary to

popular belief, he even played a Gumby (in the Gumby Brain Specialist sketch)). This tradition continued into the movies with Gilliam only appearing in small but memorable roles (e.g. Patsy in

Holy Grail, the Assistant Jailer in Life of Brian, and the poor fellow who has his liver removed in

Meaning of Life).

Post-Python

At the end of the series, Gilliam moved on to other areas, and could be found directing

T.V. commercials and title sequences for films (although he did submit animated material for ABC’s show

Marty Feldman’s Comedy Machine). When the team reunited for the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Gilliam, along with Terry Jones, took the helm. This showed him what he really wanted to do – direct. Gilliam’s first film

Jabberwocky (a film that mirrored the muddy realism of Holy Grail) was not a box-office smash (American distributors took to calling it "Monty Python’s Jabberwocky" in an attempt to sell more tickets). Despite this Gilliam moved on to his next film

Time Bandits, which was both a critical and a financial success (and allowed him to pay back George Harrison’s Handmade Films, who had underwritten both this and

Jabberwocky).

After

Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life, Gilliam moved on to the film that he considered his magnum opus –

Brazil. About an unambitious civil servant crushed by a state run by petty bureaucracy, it hailed by the critics as a masterpiece. Whilst it was released without a hitch in most countries by Twentieth Century Fox, the American distributors Universal Pictures decided they wanted a happier ending, and after making Gilliam re-edit it, refused to release it. This forced Gilliam to take out a full page advertisement in

Variety magazine reading “Dear Sid Sheinberg – When are you going to release Brazil? - Terry Gilliam”.

After

Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life, Gilliam moved on to the film that he considered his magnum opus –

Brazil. About an unambitious civil servant crushed by a state run by petty bureaucracy, it hailed by the critics as a masterpiece. Whilst it was released without a hitch in most countries by Twentieth Century Fox, the American distributors Universal Pictures decided they wanted a happier ending, and after making Gilliam re-edit it, refused to release it. This forced Gilliam to take out a full page advertisement in

Variety magazine reading “Dear Sid Sheinberg – When are you going to release Brazil? - Terry Gilliam”.

Gilliam's troubles with studio bureaucracy continued with his next film

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. The work was dogged by spiralling costs (largely the fault of producer Thomas Schüly who unwisely announced that it was going to be the biggest production since

Cleopatra (starring Liz Taylor and Richard Burton). On hearing this, all of the Italian suppliers trebled their prices). Like

Brazil, the film was not assigned any money for publicity, although in this case it was because of a campaign against the outgoing Head of Productions David

Puttnam. All of the films that were made during his tenure came in for attack, and even though Baron Munchausen

was not one of these, it was deemed to be, and so suffered along with the rest. In

fact Gilliam’s troubles were so bad that the studio only made 115 prints of the film (despite the fact that a full US release would need at least 2500).The Adventures of Baron Munchausen marked the end of Gilliam’s troubles. His next film, for the first time using a screenplay that wasn't

his own, was

The Fisher King, and was both a critical and financial success, with the film securing 4 Oscar nominations

(with actress Mercedes Ruehl winning Best Actress),a best film award at the Toronto Film Festival, and Robin Williams (playing down-and-out Parry) winning a Golden Globe.

The Fisher King contains one of Gilliam's most memorable scenes in which commuters in New York's Grand Central Station suddenly start waltzing as in a

ballroom, and then as suddenly revert to normal. His next two films – Twelve Monkeys (a dark uncompromising futuristic thriller about a time traveller sent back in time to stop a plague), and

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, (about a drug fuelled trip to Las Vegas) completed Gilliam’s rehabilitation, with both films being commercial and critical successes. Sadly his next film project

Who Killed Don Quixote never got off the ground due to a succession of disasters,

including flash floods that washed away most of his equipment, and lead actor

Jean Rochefort becoming seriously ill during filming. These catastrophes though were helpfully caught on celluloid and

were subsequently released as the most successful "unmaking of" film ever, entitled

Lost In La Mancha.

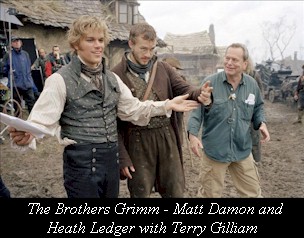

Thankfully Gilliam's bad luck was confined to that project. His next film, The Brothers Grimm (starring Matt Damon and Heath Ledger) was released to wide success. The story of travelling con artists who encounter a genuine fairy-tale curse requiring genuine courage instead of their usual bogus exorcisms took a healthy $15 million in its opening weekend. His next film Tidelands, garnered awards and nominations at the San Sebastián International Film Festival. It looked like the curse of Gilliam had struck again when star Heath Ledger died half way through filming Gilliam's movie The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus. However actors Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell and Jude Law stepped up to finish the film, in tribute to Ledger. The film was well received both critically and commercially. Gilliam's next project is a step into the unknown, as he has been signed up by the English National Opera to direct their production of Berlioz's The Damnation of Faust at the ENO's home theatre at the London Coliseum in May 2011. Rumours persist about the resurrection of Don Quixote, with the hopes that this time round, the curse of Gilliam won't strike again!

He also enjoys his hobby of (as quoted in Debrett's People of Today) "sitting extremely still for indeterminate amounts of time". For a boy from small-town Minnesota, this transformation into big-time director via the bloke who did cartoons about dancing teeth and killer cars, isn't at all bad – perhaps his high school mates got it right when they voted him 'Most Likely to Succeed'.

![]()